-

Dawn Awakens the Star PeopleWood, Paint, Steel, Granite Base

Dawn Awakens the Star PeopleWood, Paint, Steel, Granite Base- 14.5"h

- 6"w

- 5"d

$1,200 -

Star Person Looking Through the BluePainted Wood, Granite Base, Metal

Star Person Looking Through the BluePainted Wood, Granite Base, Metal- 14.5"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

$1,200 -

Pretty Woman in Her New OutfitPainted Metal, Granite Base

Pretty Woman in Her New OutfitPainted Metal, Granite Base- 17.5"h

- 5.5"w

- 6"d

$2,000 -

She Who Watches Hoop EarringsSterling Silver$200

She Who Watches Hoop EarringsSterling Silver$200 -

Star Person Feeling the Rawness of NatureWood, Paint, Abalone Shell, Glass

Star Person Feeling the Rawness of NatureWood, Paint, Abalone Shell, Glass- 8.75"h

- 4.25"w

- 2.75"d

$1,200 -

Star PersonPainted Wood, Metal

Star PersonPainted Wood, Metal- 9.5"h

- 3.75"w

- 3"d

$250 -

Shadow Spirit Head Variant EarringsSterling Silver

Shadow Spirit Head Variant EarringsSterling Silver- 1.5"h

- 1"w

Contact us to Special Order -

Shadow Spirit EarringsSterling Silver

Shadow Spirit EarringsSterling Silver- 2.5"h

- .5"w

$150 -

Star Spirit EarringsSterling Silver

Star Spirit EarringsSterling Silver- 2.25"h

- .5"w

$150 -

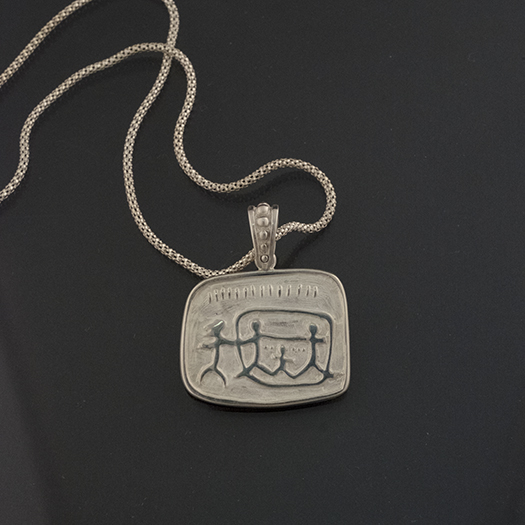

Star People PendantSterling Silver

Star People PendantSterling Silver- 3"h

- 1"w

$300 -

Star People PendantOne of a Kind Sterling Silver

Star People PendantOne of a Kind Sterling Silver- 3"h

- 1"w

$420 -

Ancient Spirit PendantSterling Silver

Ancient Spirit PendantSterling Silver- 2.25"h

- .5"w

$180 -

Shadow Spirit Head Pendant (Variant)Sterling Silver

Shadow Spirit Head Pendant (Variant)Sterling Silver- 1.18"h

$85 -

She Who Watches Pendant with Gold and PearlsSterling Silver, 18k Rose Gold, Pearls

She Who Watches Pendant with Gold and PearlsSterling Silver, 18k Rose Gold, Pearls- 1.75"h

- 1.5"w

$400 -

Koru (In Honor of the Māori) EarringsSterling Silver

Koru (In Honor of the Māori) EarringsSterling Silver- 2"h

- 1.12"w

$320 -

Koru (In Honor of the Māori) PendantSterling Silver

Koru (In Honor of the Māori) PendantSterling Silver- 1.25"h

- 1.25"w

$220 -

Grandmother Moon EarringsSterling Silver

Grandmother Moon EarringsSterling Silver- 1.75"h

- 1"w

Contact us to special order -

Sun Spirit PendantSterling Silver

Sun Spirit PendantSterling Silver- 1.5"h

$160 -

She Who Watches PendantSterling Silver

She Who Watches PendantSterling Silver- 1"h

$110 -

Shadow Spirit Head EarringsSterling Silver

Shadow Spirit Head EarringsSterling Silver- 1.5"h

- .75"w

Contact us to special order -

Dreamer Head EarringsSterling Silver

Dreamer Head EarringsSterling Silver- 1.25"h

- .5"w

- .25"d

$140 -

Mountain Goat EarringsSterling Silver

Mountain Goat EarringsSterling Silver- 1.25"h

- 1"w

Contact Us to Special Order -

She Who Watches Pin/PendantSterling Silver

She Who Watches Pin/PendantSterling Silver- 1.13"h

- 1.13"w

Contact to us to special order -

Star Person with Ribs – PurpleCast Glass, Steel, Granite Base

Star Person with Ribs – PurpleCast Glass, Steel, Granite Base- 18"h

- 6"w

- 3.75"d

$2,800 -

Moonstruck #2Wood, Paint, Steel Base

Moonstruck #2Wood, Paint, Steel Base- 14.25"h

- 5"w

- 3"d

$1,100 -

Pathfinder #1Glass, Metal Stand, Granite Base

Pathfinder #1Glass, Metal Stand, Granite Base- 17"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

$2,800 -

Star Spirit Feeling the Lake’s ReflectionWood, Paint, Abalone

Star Spirit Feeling the Lake’s ReflectionWood, Paint, Abalone- 10"h

- 3.25"w

- .53"d

$280 -

Star Spirit Feeling the Moon’s WarmthWood, Pigment, Abalone

Star Spirit Feeling the Moon’s WarmthWood, Pigment, Abalone- 12.5"h

- 4.38"w

- .38"d

$300 -

Monumental Star Spirit Feeling He Should Be Busy – Wall PieceSteel, Paint, Metal Wall Mount

Monumental Star Spirit Feeling He Should Be Busy – Wall PieceSteel, Paint, Metal Wall Mount- 80"h

- 25.25"w

- 2.18"d

$6,000 -

Giving Homage to the StarsCast Glass, Steel, Granite Base

Giving Homage to the StarsCast Glass, Steel, Granite Base- 16.75"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

$2,800 -

Star Person After Visiting Hawai’i’s Hot SpotsWood, Pigments

Star Person After Visiting Hawai’i’s Hot SpotsWood, Pigments- 9.5"h

- 3.25"w

- .63"d

$165 -

Tsagaglal (She Who Watches)Cast Red Crystal, Steel, Granite

Tsagaglal (She Who Watches)Cast Red Crystal, Steel, Granite- 18"h

- 7.5"w

- 6"d

$3,500 -

Monumental Free-Standing Star Spirit Bird Pondering His DirectionsSteel, Paint

Monumental Free-Standing Star Spirit Bird Pondering His DirectionsSteel, Paint- 72"h

- 21"w

- 13.5"d

$6,000 -

Monumental Free-Standing Star Spirit Protected From the DawnSteel, Paint

Monumental Free-Standing Star Spirit Protected From the DawnSteel, Paint- 78.5"h

- 23.5"w

- 16.63"d

$6,000 -

Monumental Free-Standing Star Spirit Dressed to Shine BrightlySteel, Paint

Monumental Free-Standing Star Spirit Dressed to Shine BrightlySteel, Paint- 77"h

- 23"w

- 14.63"d

$6,000 -

Monumental Free-Standing Star Spirit Helping the FlowSteel, Paint

Monumental Free-Standing Star Spirit Helping the FlowSteel, Paint- 75"h

- 21"w

- 14"d

$6,000 -

Star Person Appreciating BalanceMetal, Paint, Granite

Star Person Appreciating BalanceMetal, Paint, Granite- 10.5"h

- 4.25"w

- 3"d

$200 -

Star Person with Her Star ChildSteel, Copper, Beads, Granite Base

Star Person with Her Star ChildSteel, Copper, Beads, Granite Base- 11.75"h

- 4"w

- 4"d

$400 -

Star Spirit Winning the RaceSteel, Granite Base, and Paint

Star Spirit Winning the RaceSteel, Granite Base, and Paint- 11"h

- 4.25"w

- 3.25"d

$230 -

Star Spirit Just Won the RaffleSteel, Granite Base, and Paint

Star Spirit Just Won the RaffleSteel, Granite Base, and Paint- 8"h

- 4"w

- 3.25"d

$250 -

Star Spirit Youth Pondering Her FutureWood, Pigments, Copper, Push Pins

Star Spirit Youth Pondering Her FutureWood, Pigments, Copper, Push Pins- 12"h

- 4.75"w

- 1"d

$250 -

Star Spirit Feeling Like She Forgot SomethingWood, Pigments, Button

Star Spirit Feeling Like She Forgot SomethingWood, Pigments, Button- 15.5"h

- 7"w

- .5"d

$240 -

Star Person With Many TrailsWood Sculpture, Pigments

Star Person With Many TrailsWood Sculpture, Pigments- 20.25"h

- 4"w

- 1"d

$280 -

Grandmother Moon PendantSterling Silver

Grandmother Moon PendantSterling Silver- 1.25"h

$100 -

Coyote With Snout PendantSterling Silver

Coyote With Snout PendantSterling Silver- 1"h

Contact us to Special Order -

Dreamer Head Pendant (Right)Sterling Silver

Dreamer Head Pendant (Right)Sterling Silver- .75"h

$75 - Contact us to special order -

Dreamer Head Pendant (Left)Sterling Silver

Dreamer Head Pendant (Left)Sterling Silver- .75"h

Contact us to special order -

Shadow Spirit Head PendantSterling Silver

Shadow Spirit Head PendantSterling Silver- 1"h

$75 -

Abstract Coyote PendantSterling Silver

Abstract Coyote PendantSterling Silver- 1"h

$75 - Contact us to special order -

Small Coyote PendantSterling Silver

Small Coyote PendantSterling Silver- 1"h

Contact Us to Special Order -

Wolf RingSterling Silver

Wolf RingSterling Silver- 1"h

- 1.5"w

Contact us to special order -

Spider Web Jasper RingJasper, Sterling Silver

Spider Web Jasper RingJasper, Sterling Silver- 1.69"h

- 1"w

$650 -

Star Spirit Leaning Too Far Left, He Needs To Get BalancedWood, Paint, Copper, Granite Base

Star Spirit Leaning Too Far Left, He Needs To Get BalancedWood, Paint, Copper, Granite Base- 12.25"h

- 5.75"w

- 4"d

$500 -

Spirit Bird PendantSterling Silver

Spirit Bird PendantSterling Silver- 1.75"h

- .75"w

- .75"d

Contact Us to Special Order -

Star Spirit Taking a BreakSteel, Beads, Copper Wire, Granite Base

Star Spirit Taking a BreakSteel, Beads, Copper Wire, Granite Base- 9.5"h

- 5.15"w

- 4.18"d

$390 -

The Leader of the Star SpiritsSteel, Beads, Copper Wire, Granite Base

The Leader of the Star SpiritsSteel, Beads, Copper Wire, Granite Base- 8.38"h

- 4"w

- 4"d

$390 -

She Watches the Sunrise on Star PeopleBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts

She Watches the Sunrise on Star PeopleBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts- 9.75"h

- 7.75"w

- 7.75"d

$3,500 -

Star Person Checking Out the …?Steel, Beads, Granite Base

Star Person Checking Out the …?Steel, Beads, Granite Base- 10.25"h

- 4.34"w

- 3.75"d

$390 -

Teddy 3 Toes Ready To…?Steel, Copper, Beads, Granite Base

Teddy 3 Toes Ready To…?Steel, Copper, Beads, Granite Base- 11.25"h

- 5"w

- 3.5"d

$390 -

Kitty Cat Feeling…?Steel, Copper, Beads, Granite Base

Kitty Cat Feeling…?Steel, Copper, Beads, Granite Base- 8.5"h

- 5.25"w

- 2.5"d

$390 -

She Who Watches with Copper CloakCopper, Glass, Granite Base

She Who Watches with Copper CloakCopper, Glass, Granite Base- 15.5"h

- 10.5"w

- 8.5"d

$2,800 -

Star People Feeling Peaceful EnergySteel, Copper, Glass, Granite Base

Star People Feeling Peaceful EnergySteel, Copper, Glass, Granite Base- 11.25"h

- 3.75"w

- 3.75"d

$440 -

Star People Sliding Against the GrainSteel, Glass, Abalone Shell, Granite Base

Star People Sliding Against the GrainSteel, Glass, Abalone Shell, Granite Base- 9"h

- 3.75"w

- 3.75"d

$440 -

Star Person Loving the Falling StarsHigh Fired Clay with Shino Glaze, Granite Base

Star Person Loving the Falling StarsHigh Fired Clay with Shino Glaze, Granite Base- 17"h

- 5"w

- 4"d

$1,200 -

Star Person Enjoying the Swirling StarsHigh Fired Clay with Shino Glaze, Granite Base

Star Person Enjoying the Swirling StarsHigh Fired Clay with Shino Glaze, Granite Base- 15"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

$1,200 -

Fish Woman Calling All SpiritsBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts

Fish Woman Calling All SpiritsBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts- 8"h

- 6.5"w

- 7.25"d

$3,500 -

Tsagaglal (She Who Watches)- LargeLimited Edition Bronze

Tsagaglal (She Who Watches)- LargeLimited Edition Bronze- 10"h

- 13"w

- 3"d

$3,200 -

Star People Visiting the StarsBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts

Star People Visiting the StarsBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts- 9.5"h

- 8"w

- 4"d

$3,500 -

Shadow Spirits EmergingBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts

Shadow Spirits EmergingBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts- 8"h

- 6"w

- 6.75"d

$3,500 -

Sun Spirit EarringsSterling Silver

Sun Spirit EarringsSterling Silver- 1.75"h

$180 -

Spirit Bird RingSterling SilverContact Us to Special Order - Pricing will vary depending on size

Spirit Bird RingSterling SilverContact Us to Special Order - Pricing will vary depending on size -

Shadow Spirit EarringsSterling SilverContact to Special Order

Shadow Spirit EarringsSterling SilverContact to Special Order -

Reborn – With A Few FlawsMixed Media, Wood Fired Clay, Copper Wires

Reborn – With A Few FlawsMixed Media, Wood Fired Clay, Copper Wires- 15"h

- 9.5"w

- 4"d

$900 -

Reversible Chrysoprase Agate W/ Leather ChainSterling silver, Chrysoprase Agate, Leather$1,200

Reversible Chrysoprase Agate W/ Leather ChainSterling silver, Chrysoprase Agate, Leather$1,200 -

Hawk RingSterling SilverContact us to special order

Hawk RingSterling SilverContact us to special order -

Mending… To What EndWood, Ceramic, Copper Wire, Nails, Beads

Mending… To What EndWood, Ceramic, Copper Wire, Nails, Beads- 16.5"h

- 9.5"w

- 6.25"d

$1,200 -

River Spirits in SunshineMonotype Print, Framed

River Spirits in SunshineMonotype Print, Framed- 20.25"h

- 25.38"w

$900 -

Warm Springs Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast and Patinated Bronze

Warm Springs Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast and Patinated Bronze- 17"h

- 18"w

- 3.5"d

$3,000 -

Jasper Pendant on ChainJasper, Hand-pierced and Reversible Sterling Silver

Jasper Pendant on ChainJasper, Hand-pierced and Reversible Sterling Silver- 3"h

- 1.25"w

$1,000 -

Sonora Sunset Agate Pendant on Chain (Reversible)Agate, Sterling Silver

Sonora Sunset Agate Pendant on Chain (Reversible)Agate, Sterling Silver- 2.9"h

- .75"w

$1,100 -

Shield Earrings with Basket DesignSterling Silver

Shield Earrings with Basket DesignSterling Silver- 1.75"h

- 1"w

$240 -

One-of-a-Kind Stone Ring – Laguna AgateLaguna Agate, Hand-Made Sterling Silver Bezel - Size 10$960 - On Hold

One-of-a-Kind Stone Ring – Laguna AgateLaguna Agate, Hand-Made Sterling Silver Bezel - Size 10$960 - On Hold -

She Who Watches Pin/Pendant – LargeCast Sterling Silver

She Who Watches Pin/Pendant – LargeCast Sterling Silver- 1.25"h

- 1.63"w

- .5"d

Contact us to special order -

Triangle Basket EarringsSterling Silver

Triangle Basket EarringsSterling Silver- 3"h

Contact to Special Order -

Hawk Pendant with Silver Neck RingSterling Silver

Hawk Pendant with Silver Neck RingSterling Silver- 2"h

- 1.13"w

Contact Us to Special Order -

Salmon Gill Design CuffSterling Silver

Salmon Gill Design CuffSterling Silver- .75"w

Contact to Special Order -

Dreamer – Pin/Pendant (Silver)Cast Sterling Silver

Dreamer – Pin/Pendant (Silver)Cast Sterling Silver- 2.25"h

- .75"w

- .3"d

Contact Us About Special Ordering -

She Who Watches EarringsSterling SilverContact Us to Special Order

She Who Watches EarringsSterling SilverContact Us to Special Order -

Abstract Coyote Gold Pin/Pendant18kt Yellow GoldContact us to special order

Abstract Coyote Gold Pin/Pendant18kt Yellow GoldContact us to special order -

Spirit Voices – Sally Bag #10 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Spirit Voices – Sally Bag #10 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 16.75"h

- 7.5"w

- 7.5"d

$6,000 -

Ancestors’ Messages – Sally Bag #8 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Ancestors’ Messages – Sally Bag #8 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 16"h

- 13.5"w

- 13.5"d

$7,900 -

Sacred Circles PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

Sacred Circles PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order -

Sacred Circles EarringsSterling SilverContact us to special order

Sacred Circles EarringsSterling SilverContact us to special order -

Tenino Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast Bronze

Tenino Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast Bronze- 5.25"h

- 3.5"w

- 2"d

$480 -

Unique Shadow Spirit Pendant with Ocean JasperSterling Silver, Ocean Jasper

Unique Shadow Spirit Pendant with Ocean JasperSterling Silver, Ocean Jasper- 3.5"h

- .75"w

$905 -

The Dreamer Pin/Pendant (Gold)18kt Yellow GoldContact us to special order

The Dreamer Pin/Pendant (Gold)18kt Yellow GoldContact us to special order -

Crow Takes Leave of the Family Pendant – Gold18kt Yellow Gold, 22" Leather Chain with Gold ClaspContact for pricing and to order

Crow Takes Leave of the Family Pendant – Gold18kt Yellow Gold, 22" Leather Chain with Gold ClaspContact for pricing and to order -

Basket Design Earrings with AmethystsSterling Silver, Princess-Cut Amethysts, 14kt Gold Stone Settings$1,750

Basket Design Earrings with AmethystsSterling Silver, Princess-Cut Amethysts, 14kt Gold Stone Settings$1,750 -

Shield Pendant with Madeira Citrine Set in 14k GoldSterling Silver, Madeira Citrine, 14k Gold Setting$1,475

Shield Pendant with Madeira Citrine Set in 14k GoldSterling Silver, Madeira Citrine, 14k Gold Setting$1,475 -

Triangle Basket Earrings with CitrinesSterling Silver, 14k Gold Wires, 14k Gold Bezels, Citrines$2,865

Triangle Basket Earrings with CitrinesSterling Silver, 14k Gold Wires, 14k Gold Bezels, Citrines$2,865 -

One-Eyed Shadow Spirit PendantSterling Silver

One-Eyed Shadow Spirit PendantSterling Silver- 3.25"h

- 1"w

- .5"d

$550 -

Shell Spirit Pendant/PinSterling Silver

Shell Spirit Pendant/PinSterling Silver- 1.25"h

- 1"w

Contact for pricing and to order -

Small Shadow Spirit PinSterling Silver

Small Shadow Spirit PinSterling Silver- 1.75"h

Contact for pricing and to order -

Hawk Pendant with Leather Neck RingSterling Silver, Leather

Hawk Pendant with Leather Neck RingSterling Silver, Leather- 2"h

- 1.13"w

Contact for pricing and to order -

Shield Ring with Basket Pattern – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, 18k Gold Bezel, Topaz

Shield Ring with Basket Pattern – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, 18k Gold Bezel, Topaz- 2"h

- 1"w

$1,570 -

Feather Woman RingSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

Feather Woman RingSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order -

She Who Watches – RingSterling SilverContact us to special order

She Who Watches – RingSterling SilverContact us to special order -

Abstract Coyote Pin / PendantCast Sterling Silver$210

Abstract Coyote Pin / PendantCast Sterling Silver$210 -

Ancient Watcher EarringsSterling SilverContact us to special order

Ancient Watcher EarringsSterling SilverContact us to special order -

Abstract Coyote EarringsSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

Abstract Coyote EarringsSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order -

One Row of Mountains – Gold Hoop Earrings18kt Yellow GoldContact us to special order

One Row of Mountains – Gold Hoop Earrings18kt Yellow GoldContact us to special order -

Koru (In Honor of the Māori) Pendant With Iris AmethystSterling Silver, Iris Amethyst, 14k Gold$1,600

Koru (In Honor of the Māori) Pendant With Iris AmethystSterling Silver, Iris Amethyst, 14k Gold$1,600 -

Grandmother Moon Pin/PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

Grandmother Moon Pin/PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order -

Ancient Watcher PinSterling SilverContact us to special order

Ancient Watcher PinSterling SilverContact us to special order -

Crow Takes Leave From Family CuffCast and Acid-Etched Sterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

Crow Takes Leave From Family CuffCast and Acid-Etched Sterling SilverContact for pricing and to order -

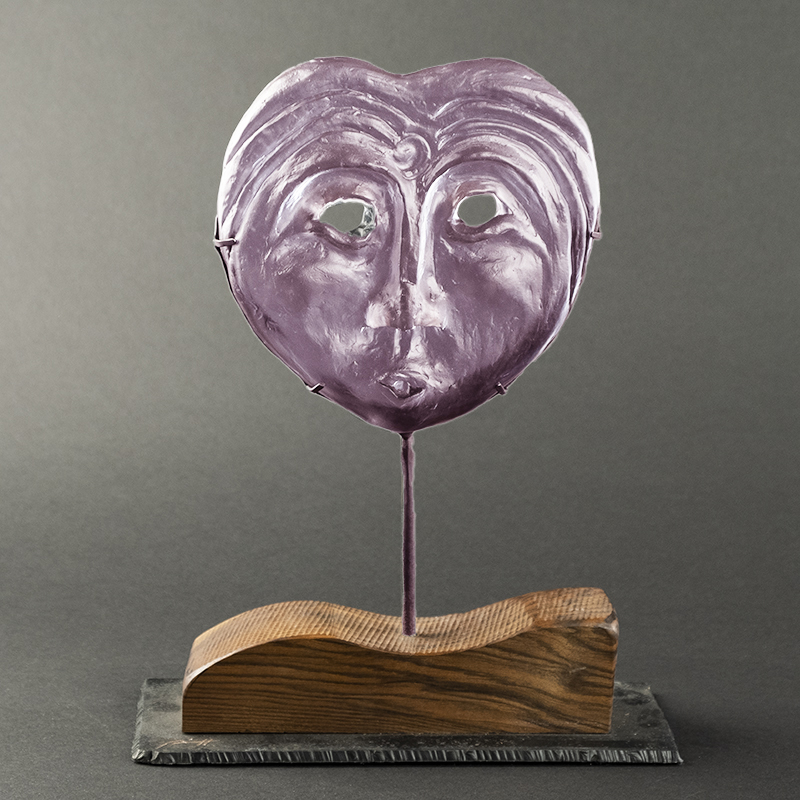

She Who WatchesCast Glass on Wood and Metal Base

She Who WatchesCast Glass on Wood and Metal Base- 10.5"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

Contact Us To Special Order -

Horse RingSterling Silver

Horse RingSterling Silver- 2.25"h

- 1"w

$500 -

Crow Takes Leave From The Family – PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

Crow Takes Leave From The Family – PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order -

Basket Design PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

Basket Design PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order -

Warm Springs Stick IndianCast Leaded Crystal on Steel Base

Warm Springs Stick IndianCast Leaded Crystal on Steel Base- 15"h

- 7"w

- 6"d

Contact to Special Order -

One-Eyed Shadow Spirit Pin/PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

One-Eyed Shadow Spirit Pin/PendantSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order -

Crow Takes Leave From The Family – EarringsSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

Crow Takes Leave From The Family – EarringsSterling SilverContact for pricing and to order

-

Star Spirit Thinking of Green ForestsPainted Wood, Abalone

Star Spirit Thinking of Green ForestsPainted Wood, Abalone- 9.5"h

- 2.5"w

- 1.5"d

SOLD -

Star Person With RibsCast Glass, Steel and Granite Base

Star Person With RibsCast Glass, Steel and Granite Base- 18"h

- 6"w

- 3.75"d

SOLD -

She Who Watches – OrangeCast Glass, Steel & Granite Base, Copper

She Who Watches – OrangeCast Glass, Steel & Granite Base, Copper- 15.5"h

- 10.5"w

- 8.5"d

SOLD -

Star PersonWood, Paint, Abalone, Steel

Star PersonWood, Paint, Abalone, Steel- 11.25"h

- 3.75"w

- 3"d

SOLD -

Star Person Feeling the Heat of the StarsWood, Paint, Steel and Granite Base

Star Person Feeling the Heat of the StarsWood, Paint, Steel and Granite Base- 19.5"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Star Person Feeling the SunriseWood, Paint, Abalone

Star Person Feeling the SunriseWood, Paint, Abalone- 12"h

- 4.25"w

- .53"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Seeing Beyond the BoundariesCedar, Paint, Abalone

Star Spirit Seeing Beyond the BoundariesCedar, Paint, Abalone- 10.25"h

- 3.5"w

- .13"d

SOLD -

Star Person Feeling GroundedWood, Paint, Elk Horn

Star Person Feeling GroundedWood, Paint, Elk Horn- 18.25"h

- 6"w

- 1.63"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Feeling the RainbowWood, Paint, Steel, Abalone

Star Spirit Feeling the RainbowWood, Paint, Steel, Abalone- 14.25"h

- 4.75"w

- 3"d

SOLD -

Star Person Getting a Little AirWood, Paint, Steel Base

Star Person Getting a Little AirWood, Paint, Steel Base- 12.75"h

- 4.75"w

- 3"d

SOLD -

Shadow Spirit Thinking of Changing Her ImageCast Glass, Steel, Granite BaseSOLD

Shadow Spirit Thinking of Changing Her ImageCast Glass, Steel, Granite BaseSOLD -

Star Person SistersWood, Shells, Paint, Steel

Star Person SistersWood, Shells, Paint, Steel- 12.75"h

- 4.5"w

- 5.63"d

SOLD -

Pathfinder #2Cast Glass, Steel, Granite Base

Pathfinder #2Cast Glass, Steel, Granite Base- 17.38"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Spirit Watcher – Raku MaskRaku-fired Ceramic with Pheasant Feathers, Copper Beads

Spirit Watcher – Raku MaskRaku-fired Ceramic with Pheasant Feathers, Copper Beads- 42.5"h

- 38.5"w

- 3.25"d

SOLD -

Star Person Awestruck by the GrassesRhubarb Glass Crystal, Granite and Steel Base

Star Person Awestruck by the GrassesRhubarb Glass Crystal, Granite and Steel Base- 16.25"h

- 6.5"w

- 4.25"d

SOLD -

Star Person Fully Dressed for the Big DanceWood, Pigments

Star Person Fully Dressed for the Big DanceWood, Pigments- 10.75"h

- 3.75"w

- .5"d

SOLD -

Star Person Feeling BlueWood, Pigments

Star Person Feeling BlueWood, Pigments- 10.63"h

- 3.13"w

- .5"d

SOLD -

Star Person Following the Flow of ThingsWood, Pigments

Star Person Following the Flow of ThingsWood, Pigments- 10"h

- 4.5"w

- .5"d

SOLD -

Star Person Dressed for the Beatles ConcertWood, Pigments, Copper

Star Person Dressed for the Beatles ConcertWood, Pigments, Copper- 8"h

- 3"w

- 1.13"d

SOLD -

Star Person Initiating Four New Stars to Find His FamilyWood, Pigments, Metal

Star Person Initiating Four New Stars to Find His FamilyWood, Pigments, Metal- 21.5"h

- 1.13"w

- 6.88"d

SOLD -

Star Person Feeling RegalCedar, Pigments, Acrylic, Shell, Metal

Star Person Feeling RegalCedar, Pigments, Acrylic, Shell, Metal- 19.75"h

- 7.25"w

- 1.5"d

SOLD -

Star Person Feeling PeacefulWood, Paint, Silver, Copper, Shell, Metal Tacks

Star Person Feeling PeacefulWood, Paint, Silver, Copper, Shell, Metal Tacks- 25.75"h

- 6.5"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

She Who Watches with Copper CloakCoast Glass (Lemon Drop Color), Copper, Granite

She Who Watches with Copper CloakCoast Glass (Lemon Drop Color), Copper, Granite- 16.5"h

- 10"w

- 10"d

SOLD -

Star Person Wanting a Tango PartnerMetal, Paint, Granite

Star Person Wanting a Tango PartnerMetal, Paint, Granite- 9.5"h

- 3.25"w

- 3.25"d

SOLD -

Star Person Having a BlastMetal, Paint, Granite

Star Person Having a BlastMetal, Paint, Granite- 10.5"h

- 3.63"w

- 3.13"d

SOLD -

Star Person Finding Her PathMetal, Paint, Granite

Star Person Finding Her PathMetal, Paint, Granite- 10.75"h

- 3.38"w

- 3.5"d

SOLD -

Star Person Finding East in the DarkMetal, Paint, Granite

Star Person Finding East in the DarkMetal, Paint, Granite- 9.25"h

- 3.25"w

- 3.88"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Dressed for the PartyWood, Steel, Copper, Glass

Star Spirit Dressed for the PartyWood, Steel, Copper, Glass- 16"h

- 7"w

- 5"d

SOLD -

From the Stars WithinWood, Metal, Paint, Steel, Granite Base

From the Stars WithinWood, Metal, Paint, Steel, Granite Base- 13.5"h

- 5.5"w

- 3.5"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Feeling the Presence of Father MoonWood, Pigments

Star Spirit Feeling the Presence of Father MoonWood, Pigments- 10"h

- 3.5"w

SOLD -

Star Spirit Catching the Lights Around HerWood, Pigments

Star Spirit Catching the Lights Around HerWood, Pigments- 16.5"h

- 4"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Wishing for a Peaceful EveningWood, Pigments

Star Spirit Wishing for a Peaceful EveningWood, Pigments- 20.25"h

- 4"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Ready for the GalaWood, Pigments

Star Spirit Ready for the GalaWood, Pigments- 25"h

- 4.5"w

- .25"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Feeling the FlowWood, Pigments, Mother of Pearl Button

Star Spirit Feeling the FlowWood, Pigments, Mother of Pearl Button- 9"h

- 3.5"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Finding the Dry LakesWood Sculpture, Pigments

Star Spirit Finding the Dry LakesWood Sculpture, Pigments- 22"h

- 8"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

Many Stars Beyond the HorizonWood Sculpture, Pigments

Many Stars Beyond the HorizonWood Sculpture, Pigments- 22.5"h

- 5.5"w

- .5"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit, Mother of the PearlWood, Pigments, Mother-of-pearl

Star Spirit, Mother of the PearlWood, Pigments, Mother-of-pearl- 17.5"h

- 7.5"w

- .5"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Happy With His New DesignsWood, Pigments, Shell, Copper

Star Spirit Happy With His New DesignsWood, Pigments, Shell, Copper- 19"h

- 6"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

Turquoise RingSterling Silver, Turquoise

Turquoise RingSterling Silver, Turquoise- 1.68"h

- 1"w

SOLD -

Star Lady with Jasper PendantSterling Silver, Jasper

Star Lady with Jasper PendantSterling Silver, Jasper- 3"h

- 2.5"w

SOLD -

Montana Agate RingAgate, Sterling Silver

Montana Agate RingAgate, Sterling Silver- 1.38"h

- 1"w

SOLD -

Star Person Finding BeautyWood, Paint

Star Person Finding BeautyWood, Paint- 15.38"h

- 4.5"w

- 1.5"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Finding BalanceWood, Paint

Star Spirit Finding BalanceWood, Paint- 18"h

- 5"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

Star Person With Her Gala OutfitWood, Buttons, Paint

Star Person With Her Gala OutfitWood, Buttons, Paint- 17"h

- 5.5"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

Star Person Loving Her New FormWood, Paint, Abalone Shell Button

Star Person Loving Her New FormWood, Paint, Abalone Shell Button- 14.5"h

- 5"w

- .5"d

SOLD -

Star Person Absorbing the Lightning StormWood, Abalone Shell, Metal

Star Person Absorbing the Lightning StormWood, Abalone Shell, Metal- 11.5"h

- 2..75"w

- 1.25"d

SOLD -

Star Spirit Mending His FlawsWood, Paint, Copper, Metal

Star Spirit Mending His FlawsWood, Paint, Copper, Metal- 12"h

- 2.5"w

- 3.5"d

SOLD -

Star Person Adjusting Her OutlookWood, Abalone, Metal, Copper, Paint

Star Person Adjusting Her OutlookWood, Abalone, Metal, Copper, Paint- 18"h

- 5"w

- 2"d

SOLD -

Star Person Enjoying the Rain DropsCast Orange Crystal, Steel and Granite Base

Star Person Enjoying the Rain DropsCast Orange Crystal, Steel and Granite Base- 19"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Ancestor’s Fish Net WeightRhubarb Glass Crystal, Steel, Wood Base

Ancestor’s Fish Net WeightRhubarb Glass Crystal, Steel, Wood Base- 8"h

- 6.25"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

She Stands Tall (Pahtu the Ancient One)Cast Glass, Wood Base, Steel

She Stands Tall (Pahtu the Ancient One)Cast Glass, Wood Base, Steel- 12"h

- 9.5"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Shadow Spirit Thinking of Changing Her ImageCast Light Blue Crystal, Wood, Steel

Shadow Spirit Thinking of Changing Her ImageCast Light Blue Crystal, Wood, Steel- 13.75"h

- 8"w

- 5.5"d

SOLD -

Many RowsCast New Zealand Lead Crystal, Steel, Granite Base

Many RowsCast New Zealand Lead Crystal, Steel, Granite Base- 18.5"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Medicine Woman for the Star SpiritsSteel, Beads, Copper Wire

Medicine Woman for the Star SpiritsSteel, Beads, Copper Wire- 8.5"h

- 5"w

- 2.75"d

SOLD -

Beginning the JourneyCast Glass, Granite Base, Steel Frame

Beginning the JourneyCast Glass, Granite Base, Steel Frame- 15.75"h

- 6.25"w

- 4.25"d

SOLD -

Fiddle Faddle, I Wanted That…Steel, Beads

Fiddle Faddle, I Wanted That…Steel, Beads- 9"h

- 4.5"w

- 2"d

SOLD -

Star People Honoring WaterHide, Birch Bark Beater, Copper Hooks, Acrylic, Tobacco as Blessing

Star People Honoring WaterHide, Birch Bark Beater, Copper Hooks, Acrylic, Tobacco as Blessing- 18"h

- 18"w

- 3"d

SOLD -

Stick Indian PinCeramic Raku, Store Bought FeathersSOLD

Stick Indian PinCeramic Raku, Store Bought FeathersSOLD -

Stick Indian PinCeramic Raku, Store Bought FeathersSOLD

Stick Indian PinCeramic Raku, Store Bought FeathersSOLD -

Stick Indian PinRaku Fired Ceramic with Store-bought FeatherSOLD

Stick Indian PinRaku Fired Ceramic with Store-bought FeatherSOLD -

Star Person Truth SeekersSteel, Copper, Abalone, Beads, Granite

Star Person Truth SeekersSteel, Copper, Abalone, Beads, Granite- 11.25"h

- 6"w

- 3.75"d

SOLD -

Star Person Bearing GiftsRed/Orange Crystal, Steel, Granite Base

Star Person Bearing GiftsRed/Orange Crystal, Steel, Granite Base- 19"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Star People WithinSteel, Copper, Beads, Granite Base

Star People WithinSteel, Copper, Beads, Granite Base- 11.25"h

- 3.75"w

- 3.75"d

SOLD -

Star People PathfinderSteel, Copper, Abalone Shell, Glass Beads, Granite Base

Star People PathfinderSteel, Copper, Abalone Shell, Glass Beads, Granite Base- 11.25"h

- 3"w

- 3"d

SOLD -

Star Child WithinSteel, Copper, Glass, Granite Base

Star Child WithinSteel, Copper, Glass, Granite Base- 11.5"h

- 3.75"w

- 3.75"d

SOLD -

Star Person Wearing Her Star ShawlHigh Fired Clay with Shino Glaze, Granite Base

Star Person Wearing Her Star ShawlHigh Fired Clay with Shino Glaze, Granite Base- 16"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Star People Visiting the WatcherBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts

Star People Visiting the WatcherBlown Glass with Glass Cutouts- 9.75"h

- 8"w

- 6"d

SOLD -

Mask Pin – HawkRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather

Mask Pin – HawkRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather- 2.13"h

- 1.88"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Red WolfRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feathers

Mask Pin – Red WolfRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feathers- 2.38"h

- 2.38"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Red WolfRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather

Mask Pin – Red WolfRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather- 1.63"h

- 1.13"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Red WolfRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather

Mask Pin – Red WolfRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather- 1.75"h

- 1.17"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – OwlRaku Fired Ceramic

Mask Pin – OwlRaku Fired Ceramic- 1.5"h

- 1.25"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Black BearRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather

Mask Pin – Black BearRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather- 1.75"h

- 1.38"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – PikaRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather

Mask Pin – PikaRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Feather- 1.63"h

- 1.25"w

SOLD -

Baby Red Wolf Maskette – Pink NoseRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Beads

Baby Red Wolf Maskette – Pink NoseRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Beads- 6.63"h

- 5.5"w

- 2.25"d

SOLD -

Baby Red Wolf Maskette with Long SnoutRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Beads

Baby Red Wolf Maskette with Long SnoutRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Beads- 7"h

- 4.75"w

- 2"d

SOLD -

Baby Red Wolf Maskette w/ AbaloneRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Beads, Abalone

Baby Red Wolf Maskette w/ AbaloneRaku Fired Ceramic w/ Beads, Abalone- 5.88"h

- 5"w

- 2"d

SOLD -

Shadow Spirits Worried About SalmonMixed Media, Reclaimed Wood, Fired Clay

Shadow Spirits Worried About SalmonMixed Media, Reclaimed Wood, Fired Clay- 38"h

- 12"w

- 3.25"d

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.63"h

- 3"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.88"h

- 2.75"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.63"h

- 2.5"w

SOLD -

She Who Watches Mask Pin W/ FeatherCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feather

She Who Watches Mask Pin W/ FeatherCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feather- 1.88"h

- 1.36"w

SOLD -

She Who Watches Mask PinCeramic Raku

She Who Watches Mask PinCeramic Raku- 1.25"h

- 1.38"w

SOLD -

Reversible Agate Pendant with Leather ChainAgate, Sterling Silver, LeatherSOLD

Reversible Agate Pendant with Leather ChainAgate, Sterling Silver, LeatherSOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.5"h

- 1.25"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.75"h

- 1.25"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.38"h

- 1.38"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.75"h

- 1.25"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.63"h

- 1.38"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.38"h

- 1.13"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 3"h

- 1.38"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.75"h

- 1.25"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Baby Red WolfCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Baby Red WolfCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.5"h

- 1.13"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – White Furred Baby SealCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – White Furred Baby SealCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 1.5"h

- 1.13"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.38"h

- 1.38"w

SOLD -

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers

Mask Pin – Stick IndianCeramic Raku, Store Bought Feathers- 2.63"h

- 1.38"w

SOLD -

Wind SpiritCast Blue New Zealand Crystal, Metal Stand

Wind SpiritCast Blue New Zealand Crystal, Metal Stand- 14"h

- 9"w

- 7"d

SOLD -

She Is Watching the Salmon RunCast Crystal, Copper, Granite

She Is Watching the Salmon RunCast Crystal, Copper, Granite- 16"h

- 8.5"w

- 7"d

SOLD -

Midnight Dance – Sally Bag #9 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Midnight Dance – Sally Bag #9 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 16.5"h

- 7.75"w

- 7.75"d

SOLD -

Sagebrush – Sally Bag #2 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Sagebrush – Sally Bag #2 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 14.75"h

- 13"w

- 13"d

SOLD -

AncestorsFused and Slumped Glass on Metal Base

AncestorsFused and Slumped Glass on Metal Base- 12.5"h

- 17.25"w

- 7.5"d

SOLD -

Unique Ring with Ocean JasperSterling Silver, Ocean Jasper - Size 8SOLD

Unique Ring with Ocean JasperSterling Silver, Ocean Jasper - Size 8SOLD -

Moonkite Jasper PendantMoonkite Jasper, Chain, Sterling Silver

Moonkite Jasper PendantMoonkite Jasper, Chain, Sterling Silver- 13.5"h

- 1.25"w

SOLD -

Reversible Sonora Sunset Pendant on ChainJasper, Sterling Silver, Leather Cord

Reversible Sonora Sunset Pendant on ChainJasper, Sterling Silver, Leather Cord- 2.75"h

- 1.25"w

SOLD -

She Who Watches FigureCast Glass, Copper, Granite Base

She Who Watches FigureCast Glass, Copper, Granite Base- 15.5"h

- 9.25"w

- 6.75"d

SOLD -

Spider WomanAnagama Fired Clay, Peacock Feathers, Beads, Shells

Spider WomanAnagama Fired Clay, Peacock Feathers, Beads, Shells- 15"h

- 17.25"w

- 2"d

SOLD -

Blue CoyoteCast Glass, Metal Base

Blue CoyoteCast Glass, Metal Base- 20"h

- 7.5"w

- 4.75"d

SOLD -

Journey #6Monoprint on Rives Paper

Journey #6Monoprint on Rives Paper- 22.25"h

- 30"w

SOLD -

She Who WatchesLimited Edition Bronze

She Who WatchesLimited Edition Bronze- 4.88"h

- 5.63"w

- .75"d

SOLD -

River GuardianCast Glass in Iron and Wood Stand

River GuardianCast Glass in Iron and Wood Stand- 18"h

- 12"w

- 5.13"d

SOLD -

Columbia River Spirits Vessel – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Columbia River Spirits Vessel – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 9.75"h

- 10.13"w

- 7.13"d

SOLD -

She Who Watches Vessel – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown, Hotsculpted and Fused Glass

She Who Watches Vessel – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown, Hotsculpted and Fused Glass- 8"h

- 8"w

- 6.5"d

SOLD -

Sunshine & Shadow Spirits Vessel – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown, Hotsculpted and Fused Glass

Sunshine & Shadow Spirits Vessel – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown, Hotsculpted and Fused Glass- 8"h

- 6"w

- 6"d

SOLD -

Spider WomanRaku, Beads, Feathers

Spider WomanRaku, Beads, Feathers- 19"h

- 18"w

- 1.5"d

SOLD -

Wily CoyoteRaku, Beads

Wily CoyoteRaku, Beads- 10.5"h

- 7"w

- 2"d

SOLD -

Montana Agate Reversible PendantMontana Agate, Sterling Silver, Woven Leather CordSOLD

Montana Agate Reversible PendantMontana Agate, Sterling Silver, Woven Leather CordSOLD -

Andean Opal on Eternity RingAndean Opal on Eternity Ring, Sterling Silver -- Size 8SOLD

Andean Opal on Eternity RingAndean Opal on Eternity Ring, Sterling Silver -- Size 8SOLD -

One-of-a-Kind Stone Ring – Arizona TurquoiseArizona Natural Turquoise, Hand-Cast Bezel - Size 9SOLD

One-of-a-Kind Stone Ring – Arizona TurquoiseArizona Natural Turquoise, Hand-Cast Bezel - Size 9SOLD -

Three Rows of Mountains EarringsSterling SilverSOLD

Three Rows of Mountains EarringsSterling SilverSOLD -

Lacy Agate RingSterling Silver, Lacy Agate - Size 7.75SOLD

Lacy Agate RingSterling Silver, Lacy Agate - Size 7.75SOLD -

Ruby Zoisite Pendant with Hammered CollarHand-Hammered Sterling Silver, Ruby ZoisiteSOLD

Ruby Zoisite Pendant with Hammered CollarHand-Hammered Sterling Silver, Ruby ZoisiteSOLD -

Basket Weave Pendant on Woven ChainSterling Silver, Leather CordSOLD

Basket Weave Pendant on Woven ChainSterling Silver, Leather CordSOLD -

Grandmother Moon Pin/PendantSterling SilverSOLD

Grandmother Moon Pin/PendantSterling SilverSOLD -

DreamerCast Bronze on Base

DreamerCast Bronze on Base- 23"h

- 7.5"w

- 7.5"d

SOLD -

Shadow Spirit Visiting Stick IndianAnagama-Fired Clay, Feathers, Beads

Shadow Spirit Visiting Stick IndianAnagama-Fired Clay, Feathers, Beads- 10"h

- 7.75"w

- 2"d

SOLD -

Jasper Stone Pendant on Leather CordJasper, Sterling Siver, Leather Cord

Jasper Stone Pendant on Leather CordJasper, Sterling Siver, Leather Cord- 2.88"h

- 1.38"w

SOLD -

Coyote and Montana Agate Pendant on CordMontana Agate, Sterling Silver, Leather Cord

Coyote and Montana Agate Pendant on CordMontana Agate, Sterling Silver, Leather Cord- 3.25"h

- 1.13"w

SOLD -

Dry Head Lake Jasper Ring – Size 7.75Dry Head Lake Jasper, Handmade Bezel Sterling Silver

Dry Head Lake Jasper Ring – Size 7.75Dry Head Lake Jasper, Handmade Bezel Sterling Silver- 2.25"h

SOLD -

She Who Watches – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

She Who Watches – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 12"h

- 8"w

- 8"d

SOLD -

Gorge Spirits – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Gorge Spirits – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 9"h

- 7"w

- 7"d

SOLD -

Firelight – Sally Bag #13 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Firelight – Sally Bag #13 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 11.5"h

- 5"w

- 5"d

SOLD -

Family Spirits – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Family Spirits – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 13.75"h

- 13.5"w

- 11.5"d

SOLD -

Violet Sky – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Violet Sky – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 14.13"h

- 14"w

- 5.5"d

SOLD -

Brush Fire – Sally Bag #4 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

Brush Fire – Sally Bag #4 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 20.75"h

- 9"w

- 9"d

SOLD -

High Summer – Sally Bag #1 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass

High Summer – Sally Bag #1 – Collaboration with Dan FridayBlown and Fused Glass- 15.75"h

- 15.13"w

- 15.13"d

SOLD -

Baby Moon Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast Bronze

Baby Moon Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast Bronze- 4.25"h

- 4.25"w

SOLD -

Kimsah Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast Bronze

Kimsah Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast Bronze- 8"h

- 6.5"w

- 2"d

SOLD -

Basket Weave Earrings with TopazSterling Silver, 14k Gold, Topaz

Basket Weave Earrings with TopazSterling Silver, 14k Gold, Topaz- 1.88"h

- .38"w

- .38"d

SOLD -

Coyote Pendant with CitrineSterling Silver, Citrine, Leather CordSOLD

Coyote Pendant with CitrineSterling Silver, Citrine, Leather CordSOLD -

Gold Water Serpent Ring18kt Yellow Gold, Size 6SOLD

Gold Water Serpent Ring18kt Yellow Gold, Size 6SOLD -

Basket Design Pendant with AmethystSterling Silver, Amethyst, 18kt Bezel on 24" Silver ChainSOLD

Basket Design Pendant with AmethystSterling Silver, Amethyst, 18kt Bezel on 24" Silver ChainSOLD -

Wasco Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast and Patinated Bronze

Wasco Stick IndianLimited Edition Cast and Patinated Bronze- 11.5"h

- 6.75"w

- 2.75"d

SOLD -

Ancestral SpiritLimited Edition Bronze

Ancestral SpiritLimited Edition Bronze- 10"h

- 8"w

- 3"d

SOLD -

Ancient OneLimited Edition Cast and Patinated Bronze

Ancient OneLimited Edition Cast and Patinated Bronze- 8.25"h

- 7.5"w

- 3"d

SOLD -

Shadow Spirit Feeling the Impressions of NatureLimited Edition Cast Bronze

Shadow Spirit Feeling the Impressions of NatureLimited Edition Cast Bronze- 12"h

- 3"w

- 3.5"d

SOLD -

Custom Eclipse EarringsSterling SilverSOLD

Custom Eclipse EarringsSterling SilverSOLD -

Oregon Coast Jasper and Agate PendantSterling Silver, Agate, Oregon Coast JasperSOLD

Oregon Coast Jasper and Agate PendantSterling Silver, Agate, Oregon Coast JasperSOLD -

She Who Watches Pendant with Pearls (Chain not included in Price)Sterling Silver, 14k Gold Discs, PearlsSOLD

She Who Watches Pendant with Pearls (Chain not included in Price)Sterling Silver, 14k Gold Discs, PearlsSOLD -

Shadow Spirit Pendant with Oregon Coast JasperSterling Silver, Oregon Coast JasperSOLD

Shadow Spirit Pendant with Oregon Coast JasperSterling Silver, Oregon Coast JasperSOLD -

Charm BraceletSterling SilverSOLD

Charm BraceletSterling SilverSOLD -

Shield Pendant with Basket Pattern – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, 18k Gold Bezel, Topaz

Shield Pendant with Basket Pattern – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, 18k Gold Bezel, Topaz- 2"h

- 1.13"w

SOLD -

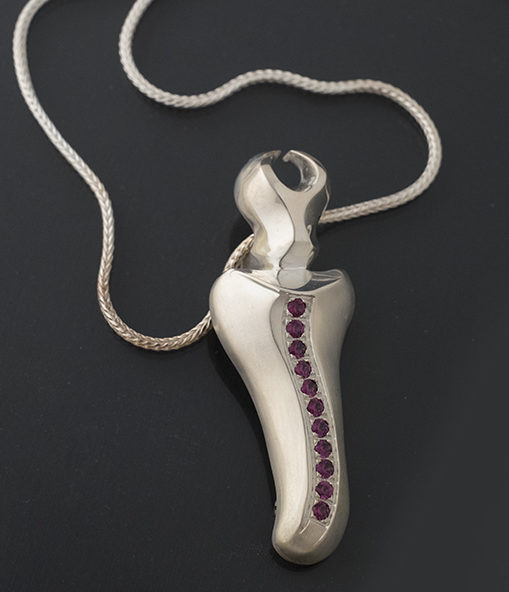

New Shadow Spirit Pendant/Pin with Grape Garnets – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, Grape Garnets

New Shadow Spirit Pendant/Pin with Grape Garnets – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, Grape Garnets- 3"h

- 1"w

SOLD -

Shadow Spirit Pendant with Citrine – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, 18k Gold Bezel, Citrine

Shadow Spirit Pendant with Citrine – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, 18k Gold Bezel, Citrine- 3"h

SOLD -

Salmon Gill Cuff with Jasper – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, Jasper

Salmon Gill Cuff with Jasper – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, Jasper- Click for dimensions"h

SOLD -

Spirit Bird Ring with Garnets – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, 14k Gold, Grape GarnetsSOLD

Spirit Bird Ring with Garnets – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, 14k Gold, Grape GarnetsSOLD -

Pendant with Mexican Opal – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, Mexican Opal

Pendant with Mexican Opal – One-of-a-KindSterling Silver, Mexican Opal- 1.13"h

SOLD -

Koru (In Honor of the Māori) Pendant with Large BailSterling Silver, Braided Leather CordSOLD

Koru (In Honor of the Māori) Pendant with Large BailSterling Silver, Braided Leather CordSOLD -

Feather Woman Pendant with Oro Verde CitrineSterling Silver, Oro Verde Citrine, 14k Gold SettingSOLD

Feather Woman Pendant with Oro Verde CitrineSterling Silver, Oro Verde Citrine, 14k Gold SettingSOLD -

Wasco CoyoteLimited Edition Bronze

Wasco CoyoteLimited Edition Bronze- 6.63"h

- 3.75"w

- 1.63"d

SOLD -

Stick Indian Healing WomanRaku, Feathers

Stick Indian Healing WomanRaku, Feathers- 18"h

- 22"w

- 1"d

SOLD -

Coyote Bronze APBronze

Coyote Bronze APBronze- 12"h

- 7"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Santiam Woman MaskCeramic

Santiam Woman MaskCeramic- 9.75"h

- 10.25"w

- 3.75"d

SOLD

Artist Statement

“I was born of the Warm Springs Reservation in Oregon over eighty years ago. My ancestors lived in the Columbia River Gorge area for over 10,000 years. My father’s people lived on the Oregon side near the great Celilo Falls. In the mid-1800’s the government moved the Washington Wasco, Wishxam, Wanapum Indians to Yakima, then switched their names to “Yakima.” The Oregon side Wasco, Wyam, Tenino, Tygh, Watlalas, were moved to Warm Springs, Oregon, then were called the “Warm Springs” Tribe. I lived in Warm Springs with my parents for twelve years before moving fifteen miles away to Madras. The day after high school graduation I moved to Portland to attend a hair styling college. After years of hairstyling, I became an instructor but had to retire because of a bad back, resulting in four back surgeries. I received my Associates of Arts degree in Mental Health/Human Services in 1981. It was during this time that I took a ceramics class. It was love at first touch! I knew then that I wanted to work in clay forever, but did not feel I was talented enough. So I made plans to continue my education in the undergraduate program in social work.

That same summer, I made seven raku-fired masks, just for the fun of it! When I heard the famous Navajo artist, R.C. Gorman, was having an opening at a local gallery, I gathered my poor quality photographs to show him, if I could muster up the courage to talk to him. I went, we talked, he asked, “What do you do?” I answered, “I make masks.” He bought two, and then convinced the gallery owner to carry the rest of my work. His generous support started me on my way in the art field. I had planned to give myself a year to give art a try; if I failed, I would go back to college.

Well, that was many years ago. I have been fortunate enough to make a living with my masks, mask pins, and multi media works ever since. My motto is the three “P’s”: patience, persistence, and perseverance. When hand-building my masks, I think of the rich history of the Columbia River Gorge, the people, the legends and stories, the animals, salmon, and all its life-giving properties. It inspires me to pay homage to it all throughout the clay process.

I was in my 30’s, and already an artist before I knew that my ancestors lived in the Columbia River Gorge for more than 10,000 years. I had no idea. That’s 8,000 years before the time of Christ, and 6,000 years before the time of the Great Pyramids at Giza! My family never spoke about it, because when I was growing up, it was better for our survival to try and cover up the fact that we were Indian. But today I can tell you that I’m proud of who I am and who my people are. We are Warm Springs, Wasco (Watalas) and Yakama (Wishxam) people — Indian people of the Pacific Northwest. We call ourselves the River People.

My early years as an artist involved learning about my heritage. We didn’t talk much about my ancestors when I was growing up, because my father thought I could have a better life if I wasn’t so Indian. So in my early years as an artist, I didn’t really know all that much about the traditional arts of my people. I wasn’t even all that sure as to whether or not I wanted to be an “Indian” artist or just an artist. But then an elder took me to see the rock carvings and paintings created thousands of years ago by my ancestors, and I was hooked. I couldn’t get over how interesting these rock images were.

So since those early years as an artist, I’ve spent a lot of time learning about my ancestors and studying the designs that they created. I learned everything I could about their rock carvings, their baskets, beaded bags, dresses, the tools they used. You name it, I’ve tried to learn about it all. But there’s so much. I don’t think I could ever learn about 10,000 years of history in just one lifetime. My art is a reflection of the Native American culture of the Columbia River Gorge. According to archeological records, the history of that region dates back at least 10,000 years.

Still, my goal is to incorporate as best I can, the traditional Native American arts of my ancestors into the contemporary art that I create. Regardless of the medium, and ever since my early years as an artist, my work directly relates to and honors my ancestors, the environment, and the animals.”

Much of Lillian Pitt’s work focuses on the ancient petroglyphs and pictographs that were carved and drawn by her ancestors in the Columbia River Gorge.

Petroglyphs are rock art engravings, and pictographs are rock art paintings. Petroglyphs and pictographs are both important parts of the rich cultural heritage of the Columbia River people. Archeologists estimate that the oldest of them in the Columbia River region could be between 6,000 and 7,000 years old. Rock art along the Columbia River include both petroglyphs and pictographs. Though no one can say for certain, official estimates are that there were roughly 90 rock art sites along the Columbia River, in the stretch of land between Pasco, Washington to the east, and The Dalles, Oregon, to the west. Unfortunately, many of these sites were either inundated or destroyed when The Dalles and the John Day dams were put into service, and are now lost to the world forever.

She Who Watches, whose Native name is Tsagaglal. Unlike most of the rock images found in the region, which are either rock etchings (petroglyphs) or rock paintings (pictographs), She Who Watches is both. Many of Lillian’s works reference the staring eyes and enigmatic expression of Tsagaglal. She sits high up on a bluff, overlooking the village of Wishxam, the village where Lillian’s great grandmother used to live. She Who Watches was the first rock image that Lillian ever saw or knew anything about, and it was only because an elder took her to see it. The elder thought it would be good for Lillian to learn something of her heritage and of her grandmother’s village.

“There was this village on the Washington side of the Columbia Gorge. And this was long ago when people were not yet real people, and that is when we could talk to the animals. And so Coyote — the Trickster — came down the river to the village and asked the people if they were living well. And they said “Yes, we are, but you need to talk to our chief, Tsagaglal. She lives up in the hill.”

So Coyote pranced up the hill and asked Tsagaglal if she was a good chief or one of those evildoers. She said, “No, my people live well. We have lots of salmon, venison, berries, roots, good houses. Why do you ask?” And Coyote said, “Changes are going to happen. How will you watch over your people?” And so she didn’t know.

And it was at that time that Coyote changed her into a rock to watch her people forever.”

-Information, writing and direct quotes copyright and courtesy of Lillian Pitt

Learn more about Lillian’s work and history in this excellent TED Talk from 2013: