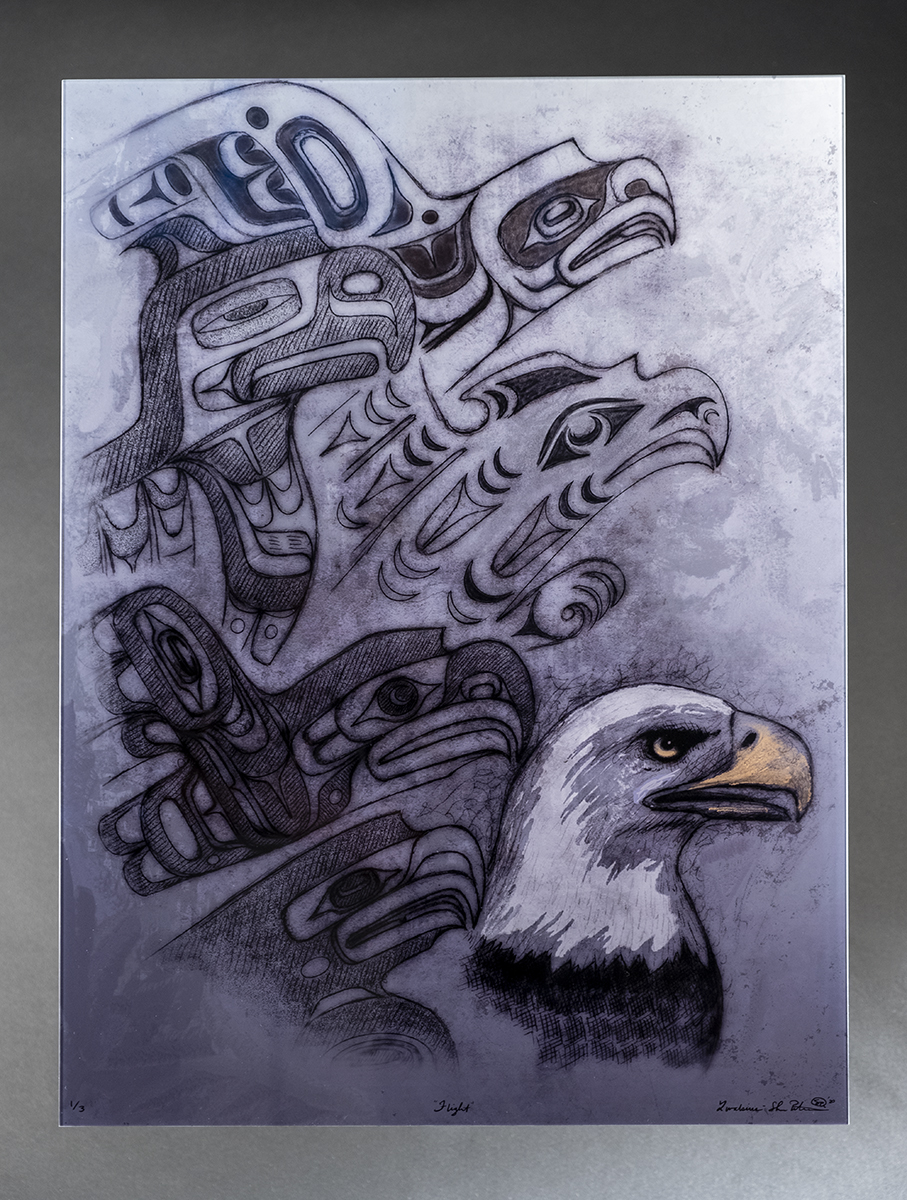

Flight

EXHIBITION:

Stonington Celebrates 40Years ago, when I started out on a decision to become an artist, I was unaware of how vast the landscape was regionally. Growing up I had been influenced by the iconography of totem poles and formline art that shaped the idea of what being Native meant. Despite a strong family connection to community, I was somewhat taken by storm to discover how diverse our cultural styles of making art were and still are. I did not start my venture into tribal art until I had graduated high school. At that time, there were few practitioners of Native art and those who were active were chasing the market. It all makes sense looking back because after all, it’s about survival.

In many ways the very practice of making or appreciating Northwest Coast Native art was just gaining traction from the efforts of Bill Reid and Mungo Martin, who helped keep the ember burning alongside individuals like Bill Holm, who has become somewhat of a Yoda figure, if we were to put ourselves into a Star Wars analogy. That said, I learned a great deal from mentor, Steve Brown by introduction of Bruce Cook III. That led me to learn and appreciate the vast stylistic and cultural expression of a universe unto it’s own. Before that I had assumed in my sheltered life that everything was red and black. Far from it, just as we know the world is not just black and white. Over time I met, and I’ve had a blessed life to learn from and work alongside many talented artists and all the while come to better understand my own journey and purpose. When people write about and simplify the relationship of Native interaction; it’s either romanticized or one of absolute opposition. Like anything, the truth lies somewhere in between and in the case of our history and differences we find ourselves in the same canoe on a journey. High tides lift us up as they say and the visibility of totem poles and formline were and remain an iconic powerful force with its own struggle to overcome over simplified views from critics.

This design comes from a page quite literally. One weekend after months of working on items to deliver for a potlatch, I was returning home with my bag of sketchbooks and a salmon rattle I was working on for my great aunt. It was a long drive and I didn’t have much sleep and as I returned to my truck the following day going to have dinner with a friend, he noticed my light on inside as we approached it. Getting closer I realized it had been broken into. The biggest regret at that moment was that I did not bother to carry the bag of sketchbooks and rattle up to my apartment. At that point the car didn’t matter near as much to me as years of work I had put onto paper. In that instance, I was beside myself and my friend brought me to my senses to at the very least look in nearby dumpsters for the bag. After all, the purpose of breaking into my car was hopes to hot-wire it and they failed. After a few hours searching, he came back with a handful of pages from one sketchbook that remained. It was the most recent of my books and nonetheless I was happy to have at least one thing. From that was a page of studies influenced by communities of and admiration for Kwakwaka’wakw, Makah, Nuu-chah-nulth, Haida, Tsimshian and Tlingit. Following that incident, I denied my initial feelings of anger, but it opened up discussion for talks with friends and family about our experiences as Native people. I look back on that with deep appreciation for those who supported me early on. My original feeling as they say ‘fight or flight’ was to fight, but with no one to fight my friend reminded me he dove into a dumpster for me and the page that survived were eagles at the ready. So, Flight took shape.