The Tlingit are the northenmost of the Northwest Coast peoples who lived traditionally by fishing and hunting marine animals and built large plank houses, totem poles, and ocean-going dugout canoes.

They were skillful traders and utilized their excess wealth on luxuries given away at splendid feasts (potlatches) which served to honor the dead and to maintain or elevate the rank of aristocrats.

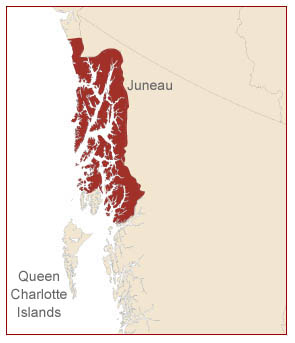

The Tlingit comprised four groups or tribes: Southern, Northern, Gulf Coast, and Inland Tlingit.

Tlingit history has been one of movement and mixing of peoples. Archeological evidence indicates an occupation of the islands and mainland of southeastern Alaska for many centuries, even millenia.

According to linguists, the Tlingit language may have split from common roots with Athapaskan about 5,000 years ago. Tlingit traditions tell of small family groups venturing in boats or rafts down the rivers under the glaciers that once arched over the waters, suggesting how early migration might have come from the interior, to mix with resident coastal populations.

Native history indicates changes in coastal populations as far back as 300 years, when Haida from the Queen Charlotte Islands moved north, displacing Tongas Tlingit, and when Northern Tlingit expanded north across the Gulf of Alaska, intermarrying with Athapaskans and exerting strong Tlingit influence on the Eyak.

Native history indicates changes in coastal populations as far back as 300 years, when Haida from the Queen Charlotte Islands moved north, displacing Tongas Tlingit, and when Northern Tlingit expanded north across the Gulf of Alaska, intermarrying with Athapaskans and exerting strong Tlingit influence on the Eyak.

(Text by Frederica de Laguna, from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History website)

On Tlingit Art:

Tlingit carvers concentrated their most decorative efforts on ceremonial and shamanic art.

Staffs, masks and rattles were decorated for potlatch songs and dances and for other rituals such as healing conducted by the shaman. The most lavishly carved eating utensils and bowls were saved for potlatches while those used for everyday meals were simply decorated.

Carved bentwood boxes stored food supplies, ceremonial clothing, or were used for cooking by dropping hot stones into a box filled with water. Huge screens, used to divide the living quarters within a house, were ornately carved, often with a family or clan crest.

Traditional totem poles depict crest figures such as animals, people, natural forms, or supernatural beings that identify a family’s history or tell important stories.

They were raised for many reasons: to dedicate a new house, commemorate a marriage, honor the deceased, or celebrate a special event. The person raising the pole told the carver which crests to use but the carver designed the pole and represented the crests as he wanted.

Raising a totem pole affirmed the status and wealth of the person and clan who commissioned the pole. Stories pertaining to the pole were told during a potlatch held to dedicate the pole.

As a result of increased wealth the peak of totem pole carving occurred in the 1860’s and then declined quickly, probably due in part to the banning of potlatches in 1884 (since repealed). The carving of house posts was abandoned in the late 19th century when Western style houses replaced communal houses. Many of the poles from the 19th century were eventually felled, destroyed, sold or removed.

For several decades the art of carving totem poles declined and appeared to be doomed. In the 1960’s an appreciation for totem poles was renewed and several Northwest Coast Native carvers revitalized the art. Most of the poles seen today are under a century old.

(Text by Barbara Waterbury, from the Sheldon Museum website.)