-

OogruqCherry Wood, Acrylic Paint, Whiskers

OogruqCherry Wood, Acrylic Paint, Whiskers- 11.25"h

- 9.5"w

- 4.5"d

SOLD -

Walrus Dancer Mask FormYellow Cedar, Pigments, Walrus Ivory, Bone Beads, Silver Wire

Walrus Dancer Mask FormYellow Cedar, Pigments, Walrus Ivory, Bone Beads, Silver Wire- 18.5"h

- 13"w

- 3"d

SOLD -

Inuit Woman at the DanceAlabaster

Inuit Woman at the DanceAlabaster- 10"h

- 6.5"w

- 9.5"d

SOLD -

Anayumalgi, Loon DancerLimited Edition Bronze

Anayumalgi, Loon DancerLimited Edition Bronze- 6.5"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

SOLD -

Giant Tufted Puffin That Eats WalrusRed Cedar, Ivory, Acrylic, Domestic Feathers

Giant Tufted Puffin That Eats WalrusRed Cedar, Ivory, Acrylic, Domestic Feathers- 20"h

- 13"w

- 9"d

SOLD -

Agnaq Traveling with Natachaq / Woman Spirit Traveling with SealRed Cedar, Yellow Cedar, Acrylic Paint, Danish Oil

Agnaq Traveling with Natachaq / Woman Spirit Traveling with SealRed Cedar, Yellow Cedar, Acrylic Paint, Danish Oil- 35"h

- 20.5"w

- 5.5"d

SOLD -

Natchiaq from Kuuk Paaruq (River Seal is My Name, From Big River)Red Cedar, Old Ivory, Acrylic

Natchiaq from Kuuk Paaruq (River Seal is My Name, From Big River)Red Cedar, Old Ivory, Acrylic- 23"h

- 16"w

- 5"d

SOLD -

Panneen, Little Girl with DollsAlabaster

Panneen, Little Girl with DollsAlabaster- 14"h

- 9"w

- 9"d

SOLD -

Out of the Mist – Loon MaskYellow Cedar, Acrylic, Glass Beads, Ivory

Out of the Mist – Loon MaskYellow Cedar, Acrylic, Glass Beads, Ivory- 17"h

- 14"w

- 11"d

SOLD -

Female Snowy Owl Spirit MaskRed Cedar, Yellow Cedar, Acrylic

Female Snowy Owl Spirit MaskRed Cedar, Yellow Cedar, Acrylic- 21"h

- 34"w

- 7.50"d

SOLD -

Ivory Raven Pendant with Chain – IOld Walrus Ivory, Ebony Wood, Sterling Silver Chain and SettingSOLD

Ivory Raven Pendant with Chain – IOld Walrus Ivory, Ebony Wood, Sterling Silver Chain and SettingSOLD -

Raven Mask – Tulugaq, SyunghaRed Cedar, Acrylic

Raven Mask – Tulugaq, SyunghaRed Cedar, Acrylic- 9.5"h

- 6"w

- 9"d

SOLD -

Kalaleet-Nunaaghitmuit Aganyat-Greenlandic WomanLimited Edition Bronze, Tanned and Dyed Seal Skin, Beads, Cedar Bark

Kalaleet-Nunaaghitmuit Aganyat-Greenlandic WomanLimited Edition Bronze, Tanned and Dyed Seal Skin, Beads, Cedar Bark- 19.63"h

- 7"w

- 8.25"d

SOLD -

Tulugaq, Raven Dancer MaskYellow Cedar, Acrylic, Feathers

Tulugaq, Raven Dancer MaskYellow Cedar, Acrylic, Feathers- 10.5"h

- 7.5"w

- 7.5"d

SOLD -

Male Seal MaskPort Orford Yellow Cedar, Pigments, Ebony, Ivory, WhiskersSOLD

Male Seal MaskPort Orford Yellow Cedar, Pigments, Ebony, Ivory, WhiskersSOLD -

Loon DancerLimited Edition Bronze

Loon DancerLimited Edition Bronze- 27"h

- 19"w

- 9.5"d

SOLD -

Loon Female Singer Spirit Mask FormRed Cedar, Acrylic Paint

Loon Female Singer Spirit Mask FormRed Cedar, Acrylic Paint- 22"h

- 26"w

- 15"d

SOLD -

Ookpik Spirit (Snowy Owl)Red Cedar, Acrylic

Ookpik Spirit (Snowy Owl)Red Cedar, Acrylic- 20.5"h

- 22"w

- 6.5"d

SOLD -

Remembering My Mother’s SongItalian Crystalline Alabaster, Wood, Ivory

Remembering My Mother’s SongItalian Crystalline Alabaster, Wood, Ivory- 20"h

- 20"w

- 20"d

SOLD -

Remembering My Song!Italian Crystalline Alabaster, Wood, Ivory

Remembering My Song!Italian Crystalline Alabaster, Wood, Ivory- 18"h

- 18"w

- 9"d

SOLD -

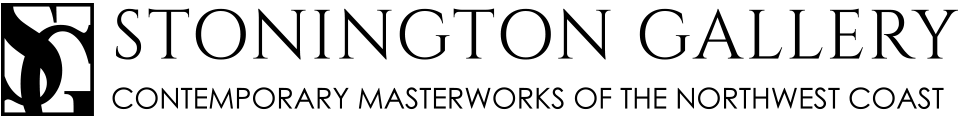

Anatkut at Winter Ceremonial Calling Seal Helping SpiritRed and Yellow Cedar, Ivory, Glass and Metal Beads, Acrylic, Ebony, Mahogany and CoaBoa Base

Anatkut at Winter Ceremonial Calling Seal Helping SpiritRed and Yellow Cedar, Ivory, Glass and Metal Beads, Acrylic, Ebony, Mahogany and CoaBoa Base- 26"h

- 7"w

- 11"d

SOLD -

Singing Seal Song (1980)African Wonderstone

Singing Seal Song (1980)African Wonderstone- 13"h

- 8"w

- 6.5"d

SOLD -

At the Celebration

At the Celebration

Seated Inupiaq WomanNew Mexican Alabaster- 13"h

- 8"w

- 9"d

SOLD -

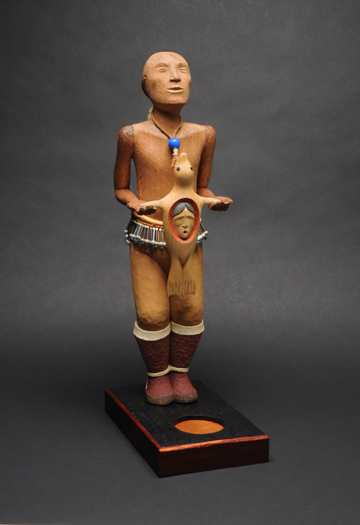

Four Night Dancers with CrossesFused Bullseye GlassSOLD

Four Night Dancers with CrossesFused Bullseye GlassSOLD -

Sculpin Female Inua/ Helping Spirit MaskWestern Red Cedar, Pigments, Feathers, Beads

Sculpin Female Inua/ Helping Spirit MaskWestern Red Cedar, Pigments, Feathers, Beads- 25.5"h

- 16.5"w

- 5"d

SOLD -

Kalaleet Nunaaghitmuit Aganyat (Greenlandic Woman)Arizona Pipestone, Seal Gut, Split Sealskin, Beads

Kalaleet Nunaaghitmuit Aganyat (Greenlandic Woman)Arizona Pipestone, Seal Gut, Split Sealskin, Beads- 21"h

- 8.5"w

- 7.5"d

SOLD -

Marbled ManWhite Marble

Marbled ManWhite Marble- 24"h

- 6"w

- 4"d

SOLD

In Larry Ahvakana’s life and art distinctions between tradition and innovation, primordial belief and socio-economic needs, enduring rituals and modern realities are unusually blurred. Widely exhibited and collected since the late 1960’s, Ahvakana’s work shifts between and bridges heritage and novelty. His art renders a way of life entwined with the past. As a Native American, he exists both at the foundation and at a distance from contemporary life and culture. Ahvakana’s authenticity and identity as an Inupiaq Eskimo is unquestioned, even as he now lives hundreds of miles to the south of where he and his forbears had always dwelled and is married to a woman from (and resides on the lands of) another Native American tribe. His ability to flourish as an artist necessitated his departure from Alaska, both to learn the arts he now excels at and to find an audience for what he does. But as surely as he needed to leave Alaska for his art, he must and does return regularly to feed his soul and reconnect with his subject, the traditional Inupiat way of life.

Ahvakana grew up within a Native heritage that did not separate artistic creativity from everyday experience. His mother was a “skin-sewer,” who created beautiful clothing for members of her community and, once she and her family moved to Anchorage, other Alaskans and tourists. His older sister is the artist Susie Bevins Qimmiqsak. Following study at the influential Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, a short bewildering stint in New York City attending the Cooper Union School of Art, and graduation from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1972, Ahvakana returned to the Northwest. Since 1980 he has been a “self-employed artist.” He has lived near Seattle for fifteen years and spends about a month each summer on his tribal land near Barrow in Beechy Point, Alaska.

From the start, even given his sophisticated training and study in the Northeast and Southwest, his unusually large stone carvings captured the quotidian needs and animating rituals of his original Eskimo hunting and fishing community. Foreboding climatic circumstances and a subsistence economy besets his subjects. A compulsively active art-maker, over the last three decades he has become adept at manipulating a variety of media that include various stones from alabaster to marble, wood, ivory, glass, bronze, and other metals and often huge preliminary drawings to realize his figures and animals.

Ahvakana’s sculptures of guardian figures, walrus deities, and winter festivals participants are perhaps more real and vital than what they portray. Like his audience, majorities of whom are – like this writer – non-Native, he venerates a culture that in the near future may only remain in the form of art. Working thousands of miles away, Ahvakana vigorously glorifies his traditions to assure they might be inherited.

– Patterson Sims, Former Curator, Seattle Art Museum

An Interview with Larry Ahvakana

Alaska Group Show 2011

SG: The move from Barrow to Anchorage marked a drastic change in your life – especially in the context of changing from a traditional Inupiaq lifestyle to a mainstream, non-traditional one. What are some traditions from your Barrow childhood that remain with you today? How have they informed and influenced your artwork?

LA: When my parents and I left Barrow and moved to Anchorage, I had just turned 6 years old. I only spoke Inupiaq with very little English. Flush toilets were a big thing. Communicating with other children and neighbors was hard, but I made friends.

The thing that stayed with me was hearing the language. I slowly lost most of my language because I was not being constantly taught; teaching was by example and my folks wanted me to learn English and be successful in the modern world. My folks both worked. My mother was a fabulous skin sewer and sold her craft and my dad was in the Army and then the National Guard.

Many people from Barrow would visit and that kept us in steady contact with the village and in a real way, the culture. They spoke Inupiaq as they talked and ate native food. I felt that the cultural influences on me seemed minimal. My folks, even while living in Anchorage, spoke Inupiaq, but encouraged me to speak English. They ate their traditional foods and practiced a subsistence way of life.

The most I incorporated my traditions (in my work) were when I attended the Institute of American Indian Arts. The instructors insisted on looking at one’s traditions for inspiration. I saw my culture differently.

SG: You now move between Barrow and Seattle each year. Does the move require a change in your mindset, or is it natural?

LA: I was again able to see and experience the traditions of dance and ceremony. Hearing my mother and father speaking Inupiaq daily was refreshing. Reconnecting to family has been invaluable. Being in Barrow throughout the year allowed me to experience village life and its year-round events and ceremonies that are still in practice, like Kivgik (the Messenger Feast) and Nalukatuk, which occurs a few weeks after a successful whale hunt and for celebrating other of life’s milestone. It also gave me time to think about my direction in art. I thought about what I previously did and I was able to see what others (artists) are doing in Barrow.

SG: If you could take any uniquely Inupiaq lessons, ethics or values and add them to non-Native mainstream culture, what would they be? How might they benefit non-Native society?

LA: Some of the most important Inupiaq values are:

Compassion: Although the environment is harsh and cold, our ancestors learned and teach to living with warmth, kindness, caring and compassion.

Avoidance of Conflict: The Inupiaq way is to think positive, act positive, speak positive and live positive.

Humor: Laughter is the best medicine!

Knowledge of Language: With our language we have an identity. It helps us to find out who we are in our mind and in our heart.

Hunting Traditions: Reverence for the land, sea and animals is the foundation of our hunting traditions.

Respect for Nature: Our Creator gave us the gift of our surroundings. Those before us placed ultimate importance on respecting this magnificent gift for their future generations.

Humility: Our hearts command we act on goodness. Expect no reward in return. This is part of our cultural fiber.

SG: Stonington’s Alaska group show opens in early August. What is August like on the tundra? Which plants and animals are active? What would the Inupiaq be doing?

LA: On the Arctic Slope, the fall season is starting with hunting for caribou, fishing with nets and gathering berries. It is also the time to get ready for whaling. Fall whaling starts in September as the migration south starts. The Tundra is browning, the weather is still predictable, however, storms are frequent and the temperature is changing from warm to cold. Typical summer temperatures can reach 60 degrees from about the middle of June through the early days of August. The typical winter temperatures range from the teens to minus 45 degrees.

SG: Much of your recent art deals with singing, music and songs. What is the role of songs in Inupiaq culture? When and where would you hear singing and drumming? Do songs hold cultural knowledge? Entertainment? Both?

LA: The emotional reverence to the activity of life is felt through ceremony and inter-relationships of all the villages on the North Slope during Kivgik, the Messenger Feast. Dance and song are intricate parts of the ceremony. The ceremony was passed down through oral history from one person to the next through families that were caretakers of the traditions. All aspects of life are reflected in the dramatic, involvement of the gatherings.

SG: Many Alaskan artisans remain in their villages carving in the traditional style. Has your experience of journeying and living in many parts of the nation influenced your choice of materials, style or themes? Do you feel that Native artists might benefit from moving locations, or conversely, from staying put? Is there a detriment to either extreme?

LA: I have always felt free to work with new materials that would give the work visual drama, or an easier way to express my ideas, but the harder materials are a challenge I welcome. Sharing ideas about images, materials, and tools is an intricate part of tradition. One is only limited by one’s knowledge and being open to learning new ways of the arts is always good. I try to express cultural experiences with my work. I feel the culture of an artist — the ways of an artist –is an integral part of the art being shown. The integration part of culture is the story and gives the artwork feeling and a place in the environment.